The positive taste of brett in wines and food matching

The line it is drawn, the curse it is cast. One of the controversies that emerged in the 1990s concerns an extremely common, but often glossed over, taste factor in wine called Brettanomyces; often shortened to “brett” in the parlance of winemakers.

Brett is basically one of the many natural species of yeast that begins to make its presence known in red wines after fermentation, while they are aging in the barrel. Although I have found few vintners anxious to discuss it, the winemaking community has long known that Brettanomyces, more than anything else, is largely responsible for the earthy, leathery qualities long associated almost exclusively with European wines, although it is by no means foreign to New World wines.

During all my years of California wine judging, in fact, picking out wines with subtle or excess brett has been as routine as picking out wines with notes of volatile acidity, oxidation, madeirization or hydrogen sulfides. Not too long ago, many wine writers and restaurant/retail professionals were still shamefully misrepresenting this attribute to consumers as aspects of terroir or climat – that is, resulting from unique environmental conditions of specific regions and vineyards – and would speak of it in reverent, and sometimes even mystical, terms.

The “glove leathery” nuances found in red Burgundy, the “sweaty saddle” common in Spanish reds and South-West French reds (like Ribera del Duero, Rioja, Madiran and Saint-Chinian), and even the handsome, leathery complexity common to many of Bordeaux’s grand crus: all of this is essentially the manifestation of a component that oenologists generally classify as a “spoilage” yeast. At worst -- when left uncontrolled in wineries (judicious use of sulfur dioxide is the most effective method of suppressing brett) – Brettanomyces laden wines begin to taste “mousy” or metallic, or else barnyardy and all-too-often, manure-like.

Brett is common to wines coming out of fairly new wine growing regions – like many cold climate grown New Zealand and Australia pinot noirs – where winemakers are just beginning to get a handle on their craft. Yet strong leather, even manure-like manifestations of brett are also common to fairly well established regions, among new and old wineries alike. Examples: cabernet sauvignons coming out of Chile (like the ultra-premium Errazuriz and Domus Aurea), Australia’s Barossa Valley (Torbreck, one of the better known of those producers), as well as California (from Robert Mondavi to Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars). Château Musar from Lebanon’s Bakaa Valley – one of the darlings of the British wine trade – is particularly rife with this character. Even more distressing is the fact that many of these high brett wines retail in the $50 to $100-plus range – as if having this stinky “European” taste qualifies for ultra-premium pricing!

Brett is common to wines coming out of fairly new wine growing regions – like many cold climate grown New Zealand and Australia pinot noirs – where winemakers are just beginning to get a handle on their craft. Yet strong leather, even manure-like manifestations of brett are also common to fairly well established regions, among new and old wineries alike. Examples: cabernet sauvignons coming out of Chile (like the ultra-premium Errazuriz and Domus Aurea), Australia’s Barossa Valley (Torbreck, one of the better known of those producers), as well as California (from Robert Mondavi to Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars). Château Musar from Lebanon’s Bakaa Valley – one of the darlings of the British wine trade – is particularly rife with this character. Even more distressing is the fact that many of these high brett wines retail in the $50 to $100-plus range – as if having this stinky “European” taste qualifies for ultra-premium pricing!

In the nineties Brettanomyces became something of a controversy within winemaking circles when more and more New World producers began to supplement their technology with traditional, Old World methods of vinification: particularly things like natural yeast fermentation, minimal sulfuring and cellar intervention, and greater tolerance of high pH levels (the level of wine’s acidic strength) than previously accepted. In wine judgings, as a result, we would find higher incidents of brett in categories such as “small production pinot noir” (case productions of, say, 500 or less). The goal, of course, was to utilize European style handcrafting to achieve more intense, unbridled natural flavors, particularly when sourced from special vineyards. Letting the terroir, so to speak, speak more loudly in the glass.

I would often find these small batch wines to be very attractive, but many others the opposite – almost repulsive. Why would many vintners deliberately skirt the fine line between subtle and excess brett; between love and hate? My personal theory: because wine writers tend to have a higher tolerance of brett than ordinary consumers (who usually believe whatever writers tell them anyway). If wines that retain, say, French-like or “rubber boot” qualities garner higher ratings from certain well known writers, why not? Do the math: high scores + critical success = greater demand, higher prices and financial success.

This is why you might read about, say, a 2006 Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste ($40-$80 current retail) that is rich, velvety, full of cigarbox and blackcurrant fruit, but also positively oozing with barnyard animal-like aromas and flavors. Yet all you read from Robert Parker (who gives it a 92) are words like “classic crème de cassis,” “pure personality,” and “beautiful density.” Jancis Robinson (who gives it 17.5 out of 20) chimes in with phraseology like “overlay of spice” and “all-over-the-palate experience.” But nary a word about the obvious brett. Why? Like I said, I think most of the better known wine writers either don’t smell it or just don’t care when they do. It’s bad enough (if you don’t enjoy the smell of barnyards in wine) that they’re swaying you by meaningless numerical scores; but when they don’t even mention it in the descriptions… don’t get me started!

This is why you might read about, say, a 2006 Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste ($40-$80 current retail) that is rich, velvety, full of cigarbox and blackcurrant fruit, but also positively oozing with barnyard animal-like aromas and flavors. Yet all you read from Robert Parker (who gives it a 92) are words like “classic crème de cassis,” “pure personality,” and “beautiful density.” Jancis Robinson (who gives it 17.5 out of 20) chimes in with phraseology like “overlay of spice” and “all-over-the-palate experience.” But nary a word about the obvious brett. Why? Like I said, I think most of the better known wine writers either don’t smell it or just don’t care when they do. It’s bad enough (if you don’t enjoy the smell of barnyards in wine) that they’re swaying you by meaningless numerical scores; but when they don’t even mention it in the descriptions… don’t get me started!

Not all writers, of course. One of the more vociferous critics of brett when it occurs in California wines has been Ronn Wiegand, an influential MW/MS. One morning he told me, “As far as I’m concerned, Brettanomyces is a serious flaw that tends to blur grape and regional distinctions. I never really liked it in French wines, and I certainly don’t think it belongs in California wines.”

There has to be some irony to the fact that after many years of being compared unfavorably to French wines, California wines are being knocked when they taste too much like them. David Ramey (pictured, right), one of the California winemakers Wiegand admires most, once shared this perspective with me: “In my experience wines that are known to be made as naturally as possible, like France’s Beaucastel and Pichon-Lalande, are often found to taste ‘better.’ No question, Brettanomyces plays a part in these wines - so where’s the problem?” At the same time, however, Ramey makes it very clear that "it's not a wise commercial policy to make wines with brett for the American market, so we have a zero brett policy here at Ramey Wine Cellars, despite working with native yeasts, high pH's and bottling unfiltered -- the classical means of elevage include techniques that eliminate brett in one's cellar."

There has to be some irony to the fact that after many years of being compared unfavorably to French wines, California wines are being knocked when they taste too much like them. David Ramey (pictured, right), one of the California winemakers Wiegand admires most, once shared this perspective with me: “In my experience wines that are known to be made as naturally as possible, like France’s Beaucastel and Pichon-Lalande, are often found to taste ‘better.’ No question, Brettanomyces plays a part in these wines - so where’s the problem?” At the same time, however, Ramey makes it very clear that "it's not a wise commercial policy to make wines with brett for the American market, so we have a zero brett policy here at Ramey Wine Cellars, despite working with native yeasts, high pH's and bottling unfiltered -- the classical means of elevage include techniques that eliminate brett in one's cellar."

Tony Soter, one of the winemakers I admire most, and whose wines at Etude were never been accused of being French-like, takes a more tolerant stance: “This is a sad issue, because it takes all the mystery out of those great French wines that, frankly, I love.” As for his own wines, Soter admits, “I’ve played with Brettanoymyces, although at relatively low levels, because it does compliment a wine somewhat. The point, however, is that ultimately it should be wine drinkers, not writers, who should decide what they like, and whether brett in a wine is good or not.”

In one of his old newsletters (now compiled in his book, Inspiring Thirst), Kermit Lynch went so far as to say that the opposite of a "bretty" wine is the type of sterile, unnatural wine he has long decried, calling the nitpicking of wines with animal, underbrush, leather or even barnyard aromas an insiduous "Attack of the Brett Nerds." Lynch has plenty to beef about because knee-jerk reactions to brett are often confused with earthy yet enthralling manifestations of garrigue - in Southern French wines in particular, time honored distinguishing marks of terroir - with this spoilage yeast; which is easy to do because of sensory similarities (for example, simply rub a twig of fresh rosemary between your fingers, and you'll retain an animal-like smell on your fingers that is pungently organic, and most definitely not brett-related).

And in fact, besides Beaucastel and Pichon-Lalande there are many, many other wines of the world that are produced with subtle qualities of brett that amplify, and thus improve, natural fruit and other organic elements, adding up to magnificent expressions of terroir: for me, the mysteriously deep, dark Madiran by Château Lafitte-Teston immediately comes to mind; so does the massively scaled Domaine de la Granges de Peres from Languedoc, the spice-box scented Gigondas by Domaine du Cayron, the magnificently deep reservas of Spain’s Tinto Pesquera, the powerful yet pillowy textured Falesco Montiano by Italy’s ingenius Riccardo Cotarella, Antinori’s legendary Tignanello, and on the home front, Randall Grahm’s groundbreaking string of Bonny Doon Le Cigare Volants… the hits go on and on.

And in fact, besides Beaucastel and Pichon-Lalande there are many, many other wines of the world that are produced with subtle qualities of brett that amplify, and thus improve, natural fruit and other organic elements, adding up to magnificent expressions of terroir: for me, the mysteriously deep, dark Madiran by Château Lafitte-Teston immediately comes to mind; so does the massively scaled Domaine de la Granges de Peres from Languedoc, the spice-box scented Gigondas by Domaine du Cayron, the magnificently deep reservas of Spain’s Tinto Pesquera, the powerful yet pillowy textured Falesco Montiano by Italy’s ingenius Riccardo Cotarella, Antinori’s legendary Tignanello, and on the home front, Randall Grahm’s groundbreaking string of Bonny Doon Le Cigare Volants… the hits go on and on.

How does that song go? If loving you is wrong, I don’t want to be right… so maybe we need to take the bull by the horns, and talk about how we can match foods with the finer brett laced wines of the world, working with the yeast to come up with something even more exciting.

IDEAL FOOD MATCHES FOR BRETT NUANCED WINES WE HAVE LOVED

Not only is Brettanomyces a welcome complexity in many wines, its presence can make for some interesting food food matches. Some guidelines and experiences:

Some brett-laced wine and food matches we have known and loved:

Brett is basically one of the many natural species of yeast that begins to make its presence known in red wines after fermentation, while they are aging in the barrel. Although I have found few vintners anxious to discuss it, the winemaking community has long known that Brettanomyces, more than anything else, is largely responsible for the earthy, leathery qualities long associated almost exclusively with European wines, although it is by no means foreign to New World wines.

During all my years of California wine judging, in fact, picking out wines with subtle or excess brett has been as routine as picking out wines with notes of volatile acidity, oxidation, madeirization or hydrogen sulfides. Not too long ago, many wine writers and restaurant/retail professionals were still shamefully misrepresenting this attribute to consumers as aspects of terroir or climat – that is, resulting from unique environmental conditions of specific regions and vineyards – and would speak of it in reverent, and sometimes even mystical, terms.

The “glove leathery” nuances found in red Burgundy, the “sweaty saddle” common in Spanish reds and South-West French reds (like Ribera del Duero, Rioja, Madiran and Saint-Chinian), and even the handsome, leathery complexity common to many of Bordeaux’s grand crus: all of this is essentially the manifestation of a component that oenologists generally classify as a “spoilage” yeast. At worst -- when left uncontrolled in wineries (judicious use of sulfur dioxide is the most effective method of suppressing brett) – Brettanomyces laden wines begin to taste “mousy” or metallic, or else barnyardy and all-too-often, manure-like.

Brett is common to wines coming out of fairly new wine growing regions – like many cold climate grown New Zealand and Australia pinot noirs – where winemakers are just beginning to get a handle on their craft. Yet strong leather, even manure-like manifestations of brett are also common to fairly well established regions, among new and old wineries alike. Examples: cabernet sauvignons coming out of Chile (like the ultra-premium Errazuriz and Domus Aurea), Australia’s Barossa Valley (Torbreck, one of the better known of those producers), as well as California (from Robert Mondavi to Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars). Château Musar from Lebanon’s Bakaa Valley – one of the darlings of the British wine trade – is particularly rife with this character. Even more distressing is the fact that many of these high brett wines retail in the $50 to $100-plus range – as if having this stinky “European” taste qualifies for ultra-premium pricing!

Brett is common to wines coming out of fairly new wine growing regions – like many cold climate grown New Zealand and Australia pinot noirs – where winemakers are just beginning to get a handle on their craft. Yet strong leather, even manure-like manifestations of brett are also common to fairly well established regions, among new and old wineries alike. Examples: cabernet sauvignons coming out of Chile (like the ultra-premium Errazuriz and Domus Aurea), Australia’s Barossa Valley (Torbreck, one of the better known of those producers), as well as California (from Robert Mondavi to Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars). Château Musar from Lebanon’s Bakaa Valley – one of the darlings of the British wine trade – is particularly rife with this character. Even more distressing is the fact that many of these high brett wines retail in the $50 to $100-plus range – as if having this stinky “European” taste qualifies for ultra-premium pricing!In the nineties Brettanomyces became something of a controversy within winemaking circles when more and more New World producers began to supplement their technology with traditional, Old World methods of vinification: particularly things like natural yeast fermentation, minimal sulfuring and cellar intervention, and greater tolerance of high pH levels (the level of wine’s acidic strength) than previously accepted. In wine judgings, as a result, we would find higher incidents of brett in categories such as “small production pinot noir” (case productions of, say, 500 or less). The goal, of course, was to utilize European style handcrafting to achieve more intense, unbridled natural flavors, particularly when sourced from special vineyards. Letting the terroir, so to speak, speak more loudly in the glass.

I would often find these small batch wines to be very attractive, but many others the opposite – almost repulsive. Why would many vintners deliberately skirt the fine line between subtle and excess brett; between love and hate? My personal theory: because wine writers tend to have a higher tolerance of brett than ordinary consumers (who usually believe whatever writers tell them anyway). If wines that retain, say, French-like or “rubber boot” qualities garner higher ratings from certain well known writers, why not? Do the math: high scores + critical success = greater demand, higher prices and financial success.

This is why you might read about, say, a 2006 Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste ($40-$80 current retail) that is rich, velvety, full of cigarbox and blackcurrant fruit, but also positively oozing with barnyard animal-like aromas and flavors. Yet all you read from Robert Parker (who gives it a 92) are words like “classic crème de cassis,” “pure personality,” and “beautiful density.” Jancis Robinson (who gives it 17.5 out of 20) chimes in with phraseology like “overlay of spice” and “all-over-the-palate experience.” But nary a word about the obvious brett. Why? Like I said, I think most of the better known wine writers either don’t smell it or just don’t care when they do. It’s bad enough (if you don’t enjoy the smell of barnyards in wine) that they’re swaying you by meaningless numerical scores; but when they don’t even mention it in the descriptions… don’t get me started!

This is why you might read about, say, a 2006 Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste ($40-$80 current retail) that is rich, velvety, full of cigarbox and blackcurrant fruit, but also positively oozing with barnyard animal-like aromas and flavors. Yet all you read from Robert Parker (who gives it a 92) are words like “classic crème de cassis,” “pure personality,” and “beautiful density.” Jancis Robinson (who gives it 17.5 out of 20) chimes in with phraseology like “overlay of spice” and “all-over-the-palate experience.” But nary a word about the obvious brett. Why? Like I said, I think most of the better known wine writers either don’t smell it or just don’t care when they do. It’s bad enough (if you don’t enjoy the smell of barnyards in wine) that they’re swaying you by meaningless numerical scores; but when they don’t even mention it in the descriptions… don’t get me started!Not all writers, of course. One of the more vociferous critics of brett when it occurs in California wines has been Ronn Wiegand, an influential MW/MS. One morning he told me, “As far as I’m concerned, Brettanomyces is a serious flaw that tends to blur grape and regional distinctions. I never really liked it in French wines, and I certainly don’t think it belongs in California wines.”

There has to be some irony to the fact that after many years of being compared unfavorably to French wines, California wines are being knocked when they taste too much like them. David Ramey (pictured, right), one of the California winemakers Wiegand admires most, once shared this perspective with me: “In my experience wines that are known to be made as naturally as possible, like France’s Beaucastel and Pichon-Lalande, are often found to taste ‘better.’ No question, Brettanomyces plays a part in these wines - so where’s the problem?” At the same time, however, Ramey makes it very clear that "it's not a wise commercial policy to make wines with brett for the American market, so we have a zero brett policy here at Ramey Wine Cellars, despite working with native yeasts, high pH's and bottling unfiltered -- the classical means of elevage include techniques that eliminate brett in one's cellar."

There has to be some irony to the fact that after many years of being compared unfavorably to French wines, California wines are being knocked when they taste too much like them. David Ramey (pictured, right), one of the California winemakers Wiegand admires most, once shared this perspective with me: “In my experience wines that are known to be made as naturally as possible, like France’s Beaucastel and Pichon-Lalande, are often found to taste ‘better.’ No question, Brettanomyces plays a part in these wines - so where’s the problem?” At the same time, however, Ramey makes it very clear that "it's not a wise commercial policy to make wines with brett for the American market, so we have a zero brett policy here at Ramey Wine Cellars, despite working with native yeasts, high pH's and bottling unfiltered -- the classical means of elevage include techniques that eliminate brett in one's cellar."Tony Soter, one of the winemakers I admire most, and whose wines at Etude were never been accused of being French-like, takes a more tolerant stance: “This is a sad issue, because it takes all the mystery out of those great French wines that, frankly, I love.” As for his own wines, Soter admits, “I’ve played with Brettanoymyces, although at relatively low levels, because it does compliment a wine somewhat. The point, however, is that ultimately it should be wine drinkers, not writers, who should decide what they like, and whether brett in a wine is good or not.”

In one of his old newsletters (now compiled in his book, Inspiring Thirst), Kermit Lynch went so far as to say that the opposite of a "bretty" wine is the type of sterile, unnatural wine he has long decried, calling the nitpicking of wines with animal, underbrush, leather or even barnyard aromas an insiduous "Attack of the Brett Nerds." Lynch has plenty to beef about because knee-jerk reactions to brett are often confused with earthy yet enthralling manifestations of garrigue - in Southern French wines in particular, time honored distinguishing marks of terroir - with this spoilage yeast; which is easy to do because of sensory similarities (for example, simply rub a twig of fresh rosemary between your fingers, and you'll retain an animal-like smell on your fingers that is pungently organic, and most definitely not brett-related).

And in fact, besides Beaucastel and Pichon-Lalande there are many, many other wines of the world that are produced with subtle qualities of brett that amplify, and thus improve, natural fruit and other organic elements, adding up to magnificent expressions of terroir: for me, the mysteriously deep, dark Madiran by Château Lafitte-Teston immediately comes to mind; so does the massively scaled Domaine de la Granges de Peres from Languedoc, the spice-box scented Gigondas by Domaine du Cayron, the magnificently deep reservas of Spain’s Tinto Pesquera, the powerful yet pillowy textured Falesco Montiano by Italy’s ingenius Riccardo Cotarella, Antinori’s legendary Tignanello, and on the home front, Randall Grahm’s groundbreaking string of Bonny Doon Le Cigare Volants… the hits go on and on.

And in fact, besides Beaucastel and Pichon-Lalande there are many, many other wines of the world that are produced with subtle qualities of brett that amplify, and thus improve, natural fruit and other organic elements, adding up to magnificent expressions of terroir: for me, the mysteriously deep, dark Madiran by Château Lafitte-Teston immediately comes to mind; so does the massively scaled Domaine de la Granges de Peres from Languedoc, the spice-box scented Gigondas by Domaine du Cayron, the magnificently deep reservas of Spain’s Tinto Pesquera, the powerful yet pillowy textured Falesco Montiano by Italy’s ingenius Riccardo Cotarella, Antinori’s legendary Tignanello, and on the home front, Randall Grahm’s groundbreaking string of Bonny Doon Le Cigare Volants… the hits go on and on.How does that song go? If loving you is wrong, I don’t want to be right… so maybe we need to take the bull by the horns, and talk about how we can match foods with the finer brett laced wines of the world, working with the yeast to come up with something even more exciting.

IDEAL FOOD MATCHES FOR BRETT NUANCED WINES WE HAVE LOVED

Not only is Brettanomyces a welcome complexity in many wines, its presence can make for some interesting food food matches. Some guidelines and experiences:

- First, there is probably nothing you can do from a culinary perspective with wines in which brett is way over-the-top – riddled with a pervasive aroma of leather to the detriment of fruitiness, or else a basically unpleasant, barnyardy stink. Excess brett – like excess alcohol, acid, volatile acidity, tannin, oak, or any other elements – will not make a dish taste better, and nothing you can do to a dish might make the wine taste better (and for you “breathers” out there: no amount of time in a decanter will rid a wine of stink either). Unbalanced wines of any sort always have a low percentage chance of working with food.

- However, wines with subtle brett qualities can be quite useful. I’ve enjoyed softer, moderately scaled reds with leather or even gamy undertones in seafood settings; particularly fish or shellfish with strong marine notes of earthy quality. Who wouldn’t, for instance, prefer a light, snappy sangiovese based red over any white wine with pasta and mussels in an herb scented tomato sauce? Earthy red Bandol is often served with bouillabaisse laced with saffron (one of the most complex earthen spices of all) to delicious effect, especially with dabs of garlicky aioli; and in the Bay Area, I’ve enjoyed some funky, small batch pinot noirs with The City’s many variations of earthy and saline cioppinos.

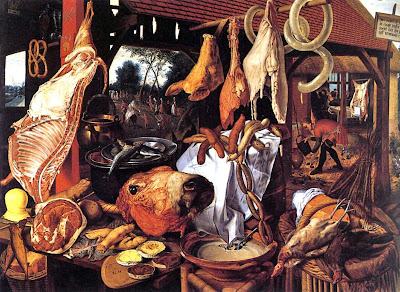

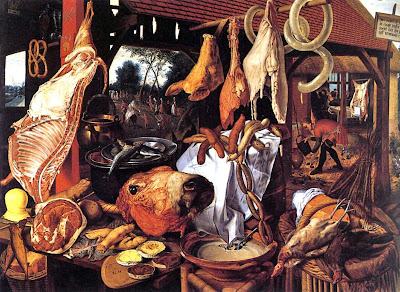

- For deeper, sturdier red wines (like cabernet sauvignon, syrah, or Southern French style blends) tinged with brett, gamy meats like venison and leg of lamb are no-brainers, and meaty birds like squab, pigeon, Muscovy duck and even goose are not a bad idea either. But you can play with lightly gamy notes in a wine with any meat, gamy or not, with the use of earthy ingredients such as wild mushrooms, organ meats, bone marrow, lardons or pancetta, homemade sausages, horseradish and fennel, root vegetables, earthy varieties of Chèvre, cumin and tumeric, and in more elegant settings, truffles (and truffle oil), foie gras, or with creative use of the trufflish Mexican delicacy, huitlacoche (corn smut, which I once enjoyed in a ravioli with crimini, spinach and achiote chili sauce).

- Use of pungent, fatty or chewy organ meats — like tripe (especially cut thick, as in meñudo), liver, kidneys, sweetbreads, tongue, beef tendons, and the rind, belly, feet, chitterlings, trotters and head meat of pork – are all of the right textural and aromatic “stuff” for earth toned wines.

- Just as use of fruit (fresh or dried) in dressings, finishing sauces, or condiments compliments a gamy meat, it goes a long ways towards brightening the fruit qualities of red wines with low key brett. Vegetables that are naturally sweet (like beets and yams) or slightly sweetened (squash and onions) can do the same.

Some brett-laced wine and food matches we have known and loved:

- In Berkeley, a succession of mildly gamy 20 year old reds (a Chave Hermitage, followed by a Vieux Télégraphe Châteauneuf-du-Pape and Domaine Tempier Bandol) with a potato casserole generously layered with black truffles

- At the Joel Palmer House in Dayton, Oregon, a pungent, essence-of-wild three-mushroom tart with a soft, fragrant, yet distinctly leather glovish Adelsheim Willamette Valley Pinot Noir

- In a South Australian wine country restaurant, a lamb’s brains in mustard sauce with a wildly earthy Rockford Basket Press Shiraz

- At Bay Wolf in Oakland, a ravioli of wild mushrooms and spinach in an aromatic porcini broth with a lush yet meaty-game nuanced Au Bon Climat Santa Maria Valley Pinot Noir

At Matsuhisa in Aspen, an ankimo (monkfish liver) paté with caviar and a bright strawberry, blackberry, pepper and leather laced Torbreck Juveniles (Barossa Valley grenache/shiraz/mataro)

- At home in the Islands, an oyster stuffed game hen in a ragout of giblets, onions and porcini with a leather-on-lace Allegrini La Grola Valpolicella

- In one of our Island restaurants, a lusty confit of duck, roasted garlic and offal in a white bean cassoulet with a mild but pungent, unsulfured, unfiltered, un-nothinged Morgon by Foillard

- In my most recent home in the Rockies, a simple cube steak pan roasted with alderwood smoked salt, cracked pepper and sweet-hot paprika – and finished with a smothering of shallots, mushrooms and red wine deglaze – with Spain’s Dehesa la Granja, brimming with sweet blackberry coated in leather and roasted meat

- Home again in the Rockies, a saddle sweat scented cumin laced ground bison chili served with Hebrew National dogs and Cheddar; finding a natural match with a virile, suede nuanced and textured Altos las Hormigas Malbec from Argentina

- One final home remedy – spinach pasta with chopped chorizo and sweet onions in classic, Italian herbed tomato sauce and generous shavings of earthy Pecorino, washed down with a zesty, leather wrapped cherry toned Peppoli Chianti Classico by Antinori

Comments